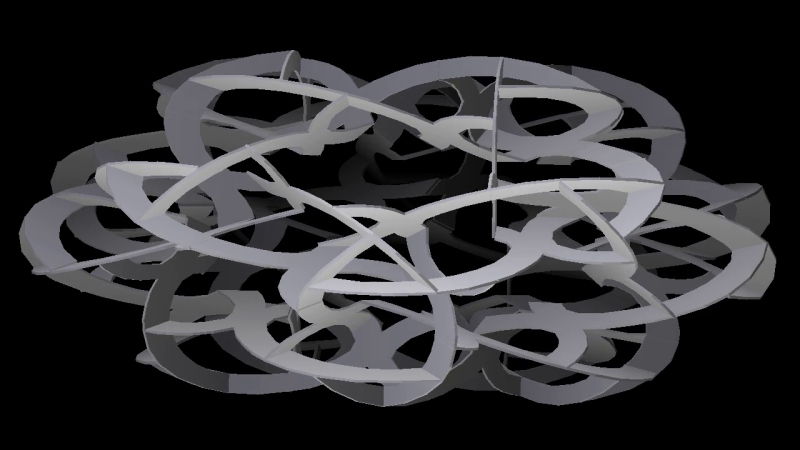

It's hard to capture

the effect of the sculpture in a still photograph.

Although they are metal, they feel like they float lightly in

the air. From some positions, one is struck by geometric

details, such as their six five-sided tunnels, one of which is

emphasized in the image above. But from other positions,

they give the impression of a 3D version of a scribbled drawing

of an amorphous cloud.

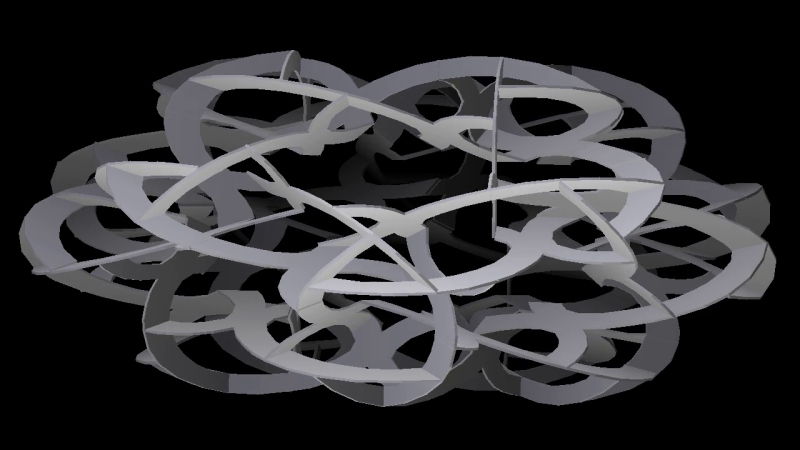

My design process is centered on

computer models, which I edit repeatedly until I'm happy with

all aspects of the design. I write my own custom software

for this, as existing 3D design packages don't have the

mathematical features I want.

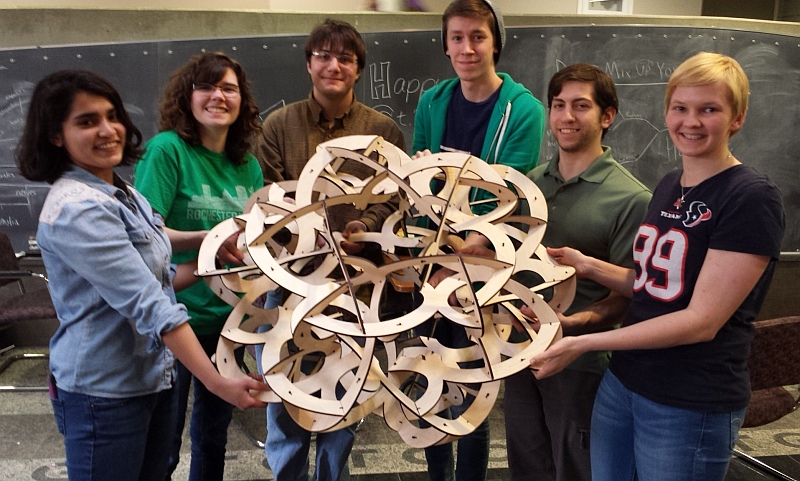

For this design, the next step was

to make a small-scale model from laser-cut plywood. I led

a group of students in this construction while visiting the

Rochester Institute of Technology. You can see the parts are

held together with small cable ties. Cable ties are great for

this because they're strong, easy to connect, and adapt to any

dihedral angle between the planes.

The next stage was to make a

full-scale wood version of both mirror-image orbs, each five

feet in diameter. These are currently on display in the

Wang Center at Stony Brook University. You need to look

carefully to observe that they make up a matched left-handed and

right-handed pair.

These are also

assembled with cable ties in a student workshop, in this case as

part of a summer math program at Stony Brook University.

This allowed me to practice the assembly sequence and work out

the best way to partition the structure into smaller modules.

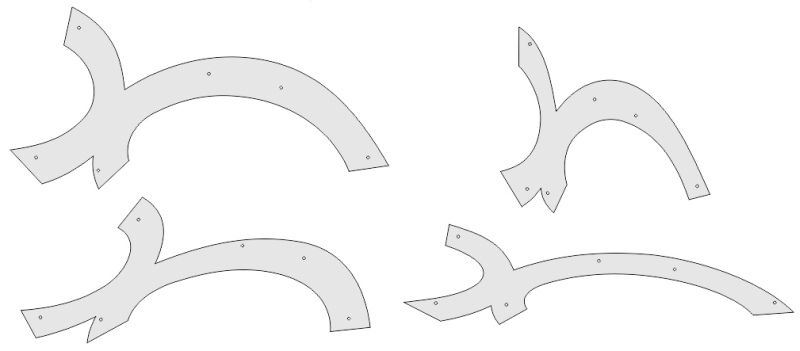

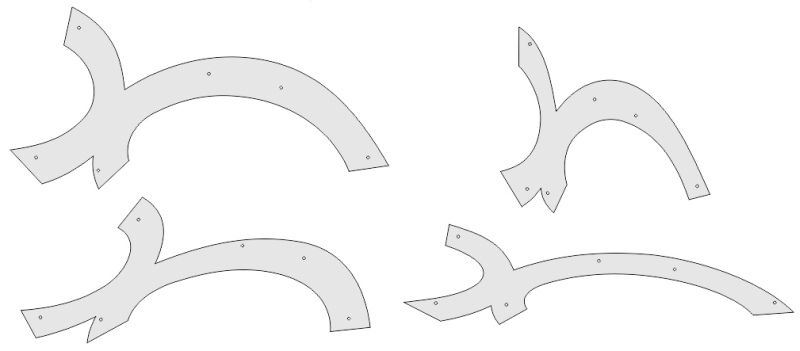

Finally, I prepared the metal parts.

They are laser-cut from aircraft aluminum in the four

different shapes shown above. The four variations are

related by affine transformations (stretching and compression

in various directions) as a result of the way the overall form

is derived. I also had to engineer the 360 brackets that

connect the pieces and work out the best locations for the

bolt holes.

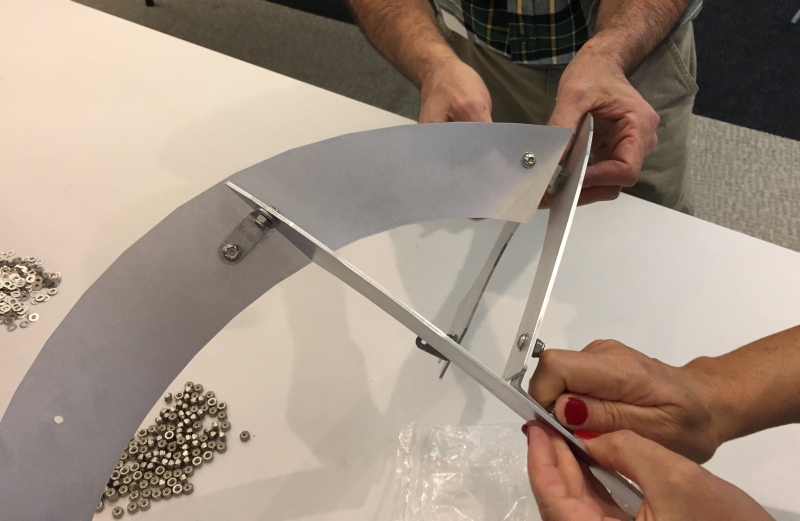

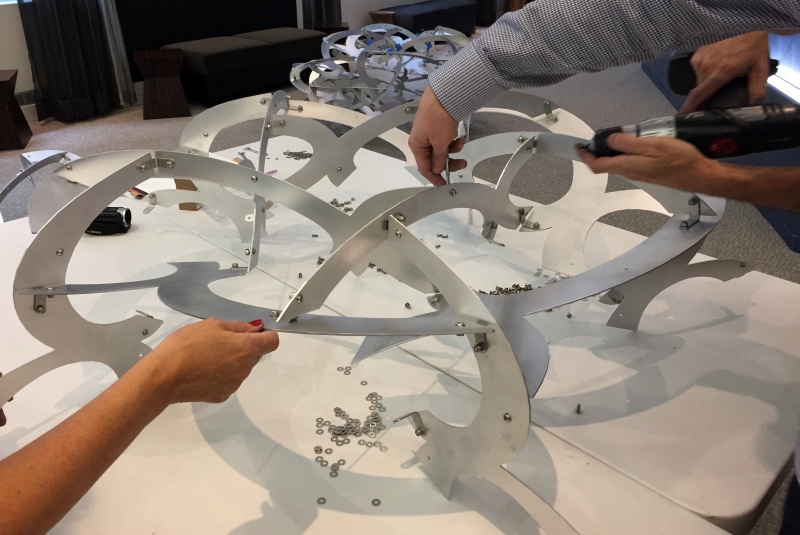

Before the day of the assembly, I attached one

side of all the brackets and connected the support cabling to

the upper pieces. The brackets had been pre-bent to

seven different angles in order to account for the various

dihedral angles between the planes. In addition to

keeping track of which bracket goes where, one must also

remember that the bracket attaches to one side or the other of

a piece depending on whether it is for the left-handed or

right-handed orb.

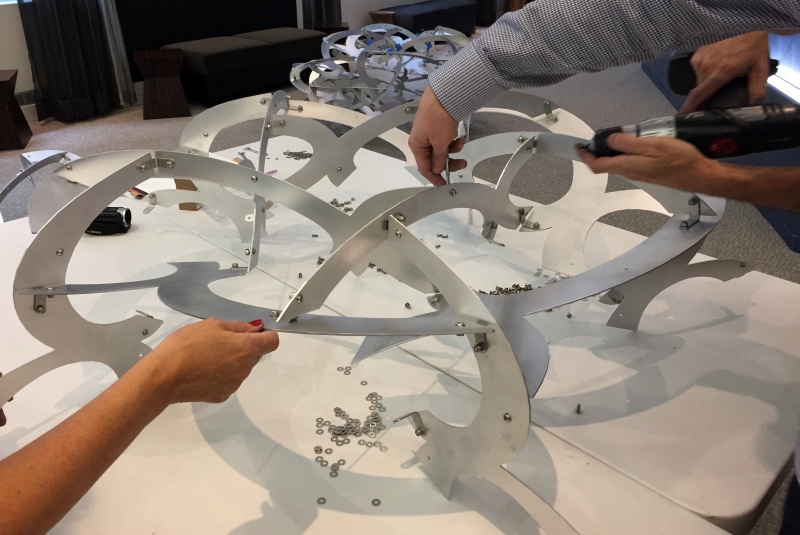

I invited some friends to help and we spent

much of a day assembling everything. The first step is

to make three-part modules, joining everything with stainless

steel nuts and bolts. The nuts have nylon inserts so

they'll never loosen, but that makes them extra troublesome to

put on. (They're sometimes called "aircraft nuts"

because they were invented to solve the problem of keeping

airplanes from falling apart from vibration.)

We make twenty of the three-part modules, as there

are sixty pieces for each orb. We also need to keep

track of the fact that there are two types (affinely related)

of module. The ones near the North and South poles are

different from the ones near the equator.

The sculpture begins to take form as we

connect the modules together. It is a wonderful feeling

to experience how everything fits together perfectly.

One advantage of laser-cutting is that it is accurate to

better than a hundredth of an inch.

For the later stages, we can work on the

floor, approaching it from all around as we continue to add

modules. Checking for loose nuts and getting everything

tight takes a while, because all together there are 720 nuts,

720 bolts, and 1440 washers to take care of.

Finally the two orbs are complete!

Hanging them was then relatively quick, as eye-bolts had been

installed in the ceiling ahead of time. Here's a view

from the floor, looking straight up, emphasizing the five-fold

rotational symmetry of the design. I'm quite proud of

the way Clouds came out.

This

video gives more information about the design and

construction process.

And you might also enjoy the rotating animation in this earlier

video.

Thank you to many people who helped me along the way, including

assembly helpers Rod Bogart, Asaka Rieser (who also took some of

the above photos), Ann Schwartz, and Jade Vinson, and many

students at Stony Brook and RIT who worked with me to build the

wood prototypes. Thank you Jamie Swan for machining the two cable

supports. Thank you Monika Lenard and Andrew Choi for

excellent local arrangements. And Thank you to the Simons

Foundation for commissioning this sculpture.