Durer's Polyhedra

Durer's Underweysung der Messung contains a very

interesting

discussion of perspective and other techniques and it typifies the

renaissance

idea that polyhedra are models worthy of an artist's

attention. More importantly, this book presents early examples

of polyhedral nets, i.e., polyheda unfolded to lie flat for

printing.

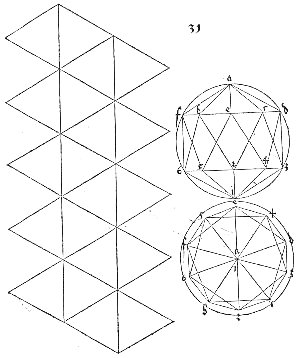

The image at right is Durer's drawing of the net of an icosahedron.

While the net is correct, his techniques of perspective were still

under

development, and it is interesting to observe that the projection at

the

upper right has a number of inaccuracies.

Here

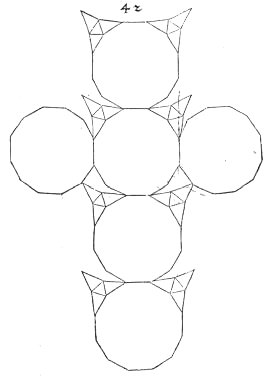

is another of Durer's nets. This is intended as a truncation

of a truncated cube. While most

of

his nets are quite accurate, this contains a significant error, which

you

will notice if you study it for a few moments. Eight of the vertices

(those

at the top left and top right of the four central dodecagons) show 360

degrees worth of angles around them, and so can not fold as intended.

This

should serve as a reminder that the idea of a net is not as simple and

obvious as one might suppose.

Here

is another of Durer's nets. This is intended as a truncation

of a truncated cube. While most

of

his nets are quite accurate, this contains a significant error, which

you

will notice if you study it for a few moments. Eight of the vertices

(those

at the top left and top right of the four central dodecagons) show 360

degrees worth of angles around them, and so can not fold as intended.

This

should serve as a reminder that the idea of a net is not as simple and

obvious as one might suppose.

An interesting property of this polyhedron, which might be why

Durer

included it, is this: if the dodecagons are regular then it can be

inscribed

in a sphere.

The

Underweysung

der Messung is also significant because it

contains

the first presenation of the snub

cube.

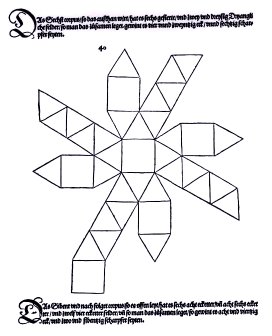

The snub cube is the first of the chiral Archimedean

solids to be rediscovered in the Renaissance. (The other, the

snub

dodecahedron, had to wait for Kepler.)

Given the chirality of the snub cube, it strikes me as strange that

Durer

did not give a picture of the solid itself or mention its two

forms.

He contented himself with the net at right.

The

Underweysung

der Messung is also significant because it

contains

the first presenation of the snub

cube.

The snub cube is the first of the chiral Archimedean

solids to be rediscovered in the Renaissance. (The other, the

snub

dodecahedron, had to wait for Kepler.)

Given the chirality of the snub cube, it strikes me as strange that

Durer

did not give a picture of the solid itself or mention its two

forms.

He contented himself with the net at right.

One

of Durer's masterpieces, the engraving Melancholia I, features

a frustrated

thinker sitting by an uncommon polyhedron. (Click the image for a larger

version.) Much has been written analyzing the symbolism in the

image

and the possible meaning of every element including the polyhedron. One

might speculate that the cube represents masculinity and truncating one

in an upright position may have some Freudean symbolism.

One

of Durer's masterpieces, the engraving Melancholia I, features

a frustrated

thinker sitting by an uncommon polyhedron. (Click the image for a larger

version.) Much has been written analyzing the symbolism in the

image

and the possible meaning of every element including the polyhedron. One

might speculate that the cube represents masculinity and truncating one

in an upright position may have some Freudean symbolism.

Geometrically, the polyhedron is simply a cube or rhombohedron which has been truncated at the upper vertex. (I can not decide if the lower vertex is also truncated so the solid rests on a triangular face, or if the lower vertex symbolically penetrates the earth, but no other writers seem to allow for that possibility.) Panofsky accurately describes it simply as a "truncated rhomboid." It is possible to proportion it so that the vertices project onto a 4-by-4 square grid like that of the magic square (see the papers by Lynch and Sharp). Schreiber proposes that it comes from a rhombohedron with 72-degree face angles, which has been truncated so it can be inscribed in a sphere. This polyhedron continues to sire a considerable literature, so for those who wish to read some of what has been written about it, here are a few references to get you started:

- P. J. Federico, "The Melancholy Octahedron," Mathematics Magazine, pp. 30-36, 1972.

- T. Lynch, "The geometric body in Durer's engraving Melancholia I," Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Inst., pp. 226-232, 1982.

- C. H. MacGillavry, "The Polyhedron in A. Durer's 'Melancolia I': An Over 450 Years Old Puzzle Solved ?" Netherland Akad Wetensch. Proc., 1981.

- E. Panofsky, The Life and Art of Albrecht Durer, Princeton, 1955.

- P. Schreiber, "A New Hypothesis on Durer's Enigmatic Polyhedron in His Copper Engraving 'Melencholia I'," Historia Mathematica, 26, pp. 369-377, 1999.

- K. D. Walton, "Albrecht Durer's Renaissance Connections Between Mathematics and Art," The Mathematics Teacher, pp. 278-282, 1994.

- J. Sharp, "Durer's Melancholy Octahedron," Mathematics in School, Sept. 1994, pp. 18-20.